All That’s Not Said

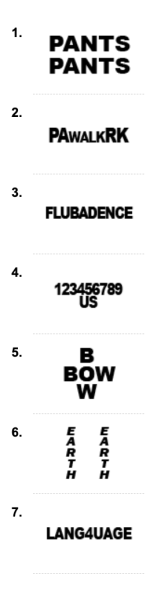

My mother is meticulous. She walks briskly from task to task, looking backward only to make sure her footsteps are in perfect order. I’ve never seen her cry – oh no, that would be just too messy. She doesn’t snore or talk in her sleep. My mother is a bow and arrow, the shooter and the shot, projecting herself past winds and waters to land, exactly at the designated coordinates on the opposite bank. When I look at her, compare the furrowed brow of concentration to the smiling rosy women in the laundry commercials, I know she’s different. My friends’ mothers are vivacious and noisy and sometimes bossy, but their jokes are the perfect mediators for residual tension; their chocolate cake smiles are goofy and yes, a little bit gross, but pleasantly so. I saw my best friend’s mom cry once; it was at a movie of all things! The girlfriend had died of some disease or another and I watched, stony-faced, as the boyfriend mumbled through a speech at her funeral while the walls of the theater shook with the pressure of held-back sobs. He was crying, my best friend was crying, her mom was crying, hell, even the janitor sent in to clean up spilled popcorn had silent tears running down his cheeks. But I’d been conditioned well.

“Don’t cry, Karen,” she would say, after I fallen off my bike or been not-so-politely rejected by a crush. “Crying doesn’t do anything. You’ll feel better if you just don’t think about it.” I was seven and my knees were bleeding, but that didn’t stop me from trying. So I sat on the floor and played with my stuffed animals, ignoring the sting of raw skin on carpet, letting the tears dry on my cheeks.

My dad died when I was four. Cancer, I was told. I remember him in fragments, enough to pick up off the ground and fit together, but the pieces missing are large and visible. I remember a toothy grin, a set of arms spinning me in circles until I flew, my hair and feet streaming like they were chasing after me. I remember toppling gently on the grass and screaming, “Again! Again!” His nose: long, straight; his name, of course: Thomas, an elegant, forthright name; his eyes: perpetually smiled into joyful slits; his laugh: full-bellied, a laugh that could fill up a room. I remember bits of my mother over his shoulder, laughing along with us, yet always careful to dust off the back of my shorts before I sat down at the table for a snack. I think they were each other’s middle ground. She kept him moving forward with gentle reminders of to-do’s and appointments and dishes that needed to be washed. He kept her laughing, gave her some comfort that things would get done and she didn’t always have to be the one to do them. I don’t remember the shape of his ears or the way he ran or what his voice sounded like, but I have enough puzzle pieces to get me by.

One day last spring, Mom went to the doctor’s – a reluctant move, as she was sure that she could cure whatever was ailing her by concentration alone– and I decided that some snooping was in order. Going through her dresser, I was careful, so so careful, putting jewelry boxes back at their original angle, making sure not to disturb the meticulously folded dress shirts. In the sock drawer I found three condoms, their expiration dates about as old as I was. In the underwear drawer I found a diary.

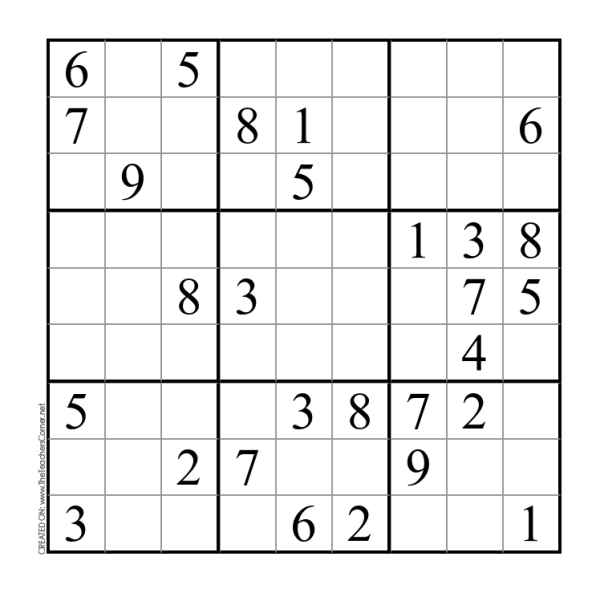

It wasn’t locked like I thought it would be. Plain, black moleskin, “J. Myer” lettered in crisp handwriting on the upper inside cover. The first page was empty. The second page had only numbers, scrawled haphazardly, often intersecting and veering up or down, falling off the borders to become scribbles. 3, 3, 1, 9, 12, 10, 18, 25, 25, 30, 31. Working to understand this seemingly random set, I flipped to the next page and found more. 16, 19, 18, 25, 37, 50, 42, 43, and so on. I rifled through the journal, finding nothing but page after page of numbers. Frustrated with the lack of information I had found in what was supposed to be the most personal of locations, I turned to the last page of the book. Written in shaky, barely legible script, I made out Times per day I think about Tom. 2006–2015.

She came home from the doctor’s an hour or so later — “It wasn’t strep, just a virus. I could’ve predicted that!” And set about wiping down the counters and pushing in chairs, always ready for some invisible guest. I had replaced the diary in its precise location, arranged the underwear around it, and closed the drawer, aware of the ghosts that followed me as I padded out of the room and quietly shut the door.

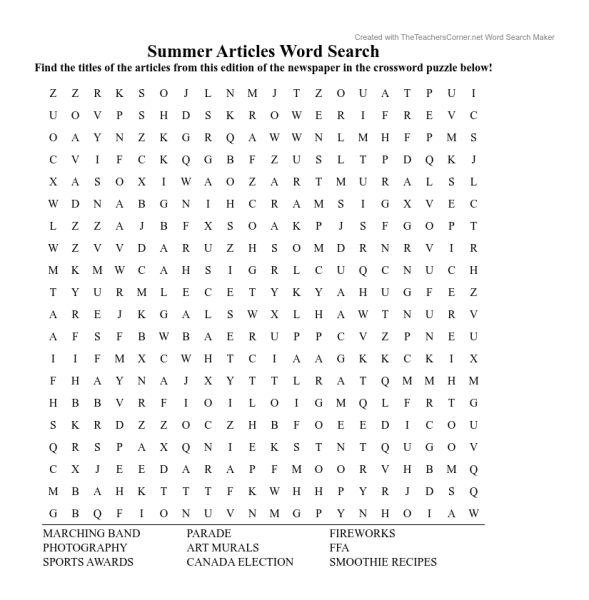

She made dinner and we ate, exchanging pleasantries and not much else. As we exhausted our supply of comments about the vegetables and the weather, the clatter of silverware turned our silence into radio static, that nothing noise that fills ears and brains.

“Do you miss Dad?” I finally asked, casually putting down my fork and resting my elbows on the table, an action sure to spur a chiding remark. Her head snapped up from her plate to me, examining my face for hidden meaning, trying to find out what I wasn’t saying. Seeing that I was simply curious, oblivious to the assault weapon of knowledge I held behind my eyes, she returned to her food, arching her back to maintain a dignified posture. “Occasionally. It’s only natural. But if you don’t think about it too much, it goes away, just like everything else.” I thought back to the numbers in that soft little book, starting in single digits. By the final page, probably filled out just months ago, they were up to several hundred. “Karen?” She murmured, pulling me from my thoughts. She was staring intently at my face, as if seeing it for the first time.

“Yes, Mom?”

“Take your elbows off the table. It’s rude.”