On the Hunt for Aliens Again

September 30, 2017

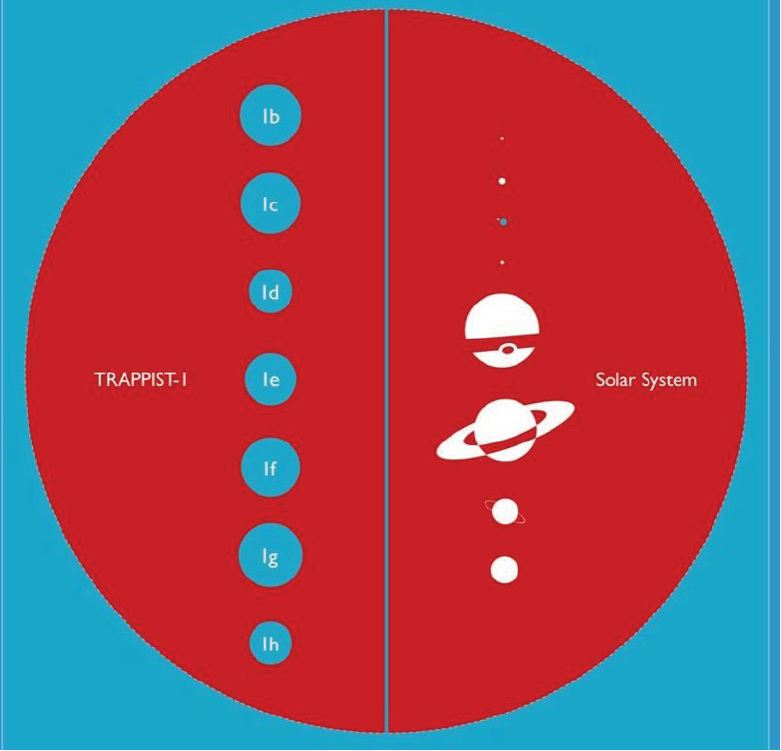

Far, far away in the constellation Aquarius, lives TRAPPIST-1, an ultracool red dwarf star with seven orbiting, Earth-size planets. You’ve likely heard of this newfound system by now as it made headlines on February 22 with its truly intriguing features. 39 light years from Earth, TRAPPIST-1 boasts the largest number of Earth-sized, assumably rocky exoplanets (planets outside of our solar system) to date. Of these planets, three lie in the “habitable zone,” in which, given the right atmospheric conditions, there exists the potential to host liquid water on their surfaces.

We all know what this means: aliens! Well, not so fast, buddy.

At the present moment, there isn’t enough data available to find any extraterrestrial friends. TRAPPIST-1 is about 8 percent the size of the Sun and much dimmer, making it difficult to spot even with large amateur telescopes. The planets’ atmospheric and geological traits are still relatively unknown.

But fear not, detailed data on this system is bound to arrive around 2020 as NASA’s Webb Space Telescope, launching in 2018, will be able to get a closer look at the planets and report on the temperature and composition of their atmosphere.

Though similar in size to Earth, these planets are not under the same circumstances as our home planet. A full orbit around their red dwarf lasts between one and a half to twenty days whereas Earth’s orbit around the Sun lasts 365. The planets are comparably much closer to their star which most likely means they will orbit with one side always facing the red dwarf. Not only that, but TRAPPIST-1 does not emit the same type of wavelength of light as the Sun. Being a red dwarf, it emits longer wavelengths, nearing infrared.

Scientists were eager to jump on the opportunity to learn more about this incredible discovery and Eric Wolf, a researcher at University of Colorado, Boulder, was no exception. Wolf recently created in-depth atmospheric models of three of the planets, testing potential climates to find out if any of them would support liquid water on the surface. Taking into consideration radiation, cooling impact from clouds, and the effect of several gases, Wolf narrowed down the possibility of sustaining water down to one planet, TRAPPIST-1e.

Wolf concluded that planet d (creative names, I know) is too close to its star, making it impossible for water to remain on the surface. The atmosphere of water vapor would further warm the planet, causing any remaining water to boil off. On the contrary, planet f is much too far from the star; any water would be frozen solid in the bitter cold. Wolf attempted to add gases to his model to see if f would ever be warm enough to sustain water, but he found that even after adding 30 times the Earth’s pressure in carbon dioxide at sea-level to the model, the results remained icy.

E proved to be the only habitable planet. Wolf found that, with an Earth-like atmosphere, 20 percent of the planet remained warm enough to avoid freezing over, and discovered that by adding more carbon dioxide and nitrogen, he could duplicate Earth’s atmosphere.

As powerful telescopes provide more data about the system to compare to these models, scientists will be able to reach a consensus and uncover the truth about these captivating planets. I suppose we’ll have to wait and see.